Where next for VCTs?

After a decade of strong performance, Nick Britton looks at risks to the sector.

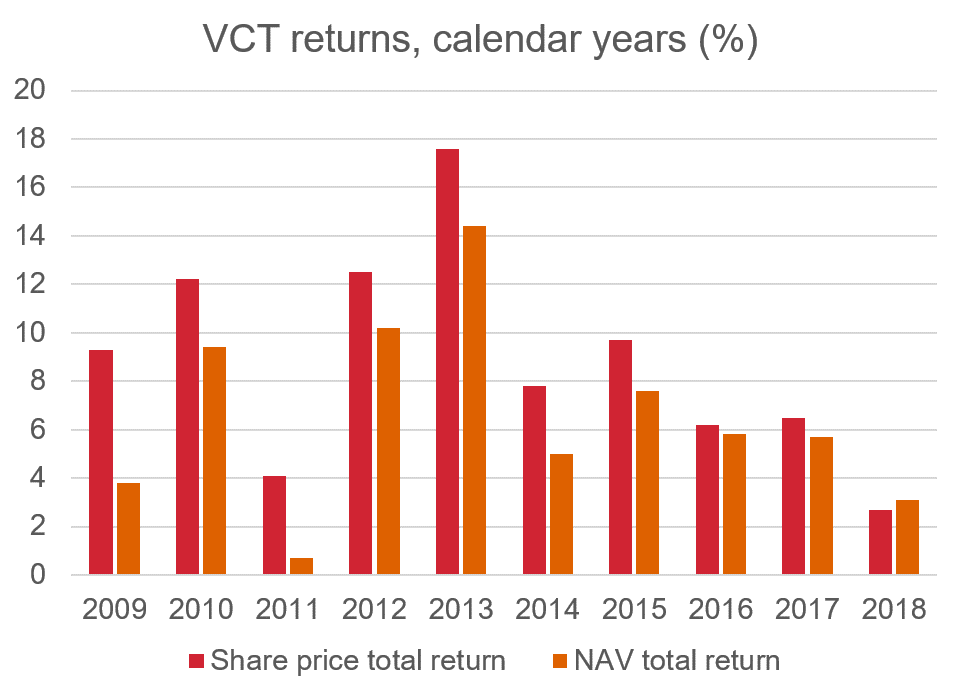

There are only two investment company sectors that have delivered positive returns for each of the past ten calendar years, on both a share price and NAV basis. One is infrastructure, which perhaps isn’t surprising. The other is VCTs.

There are only two investment company sectors that have delivered positive returns for each of the past ten calendar years, on both a share price and NAV basis. One is infrastructure, which perhaps isn’t surprising. The other is VCTs.

It’s worth taking a moment to reflect on that. VCTs invest in small, fragile companies. Many of these will fail. Positive returns depend largely on being able to sell companies on for a profit, over an uncertain timescale.

So why have returns been so consistent? Before we get carried away, we should remember that not all VCTs have delivered ten years of positive returns; it’s only the sector average that has been positive in each year. We should also add that returns were not positive in 2008. Nevertheless, ten years without a loss is surprising when we consider the usual profile of venture capital returns, which are prone to ‘hockey stick’ or ‘J-curve’ effects even in the best-case scenario.

One reason that VCTs have been able to beat the J-curve is their evergreen structure. This is unusual in the world of venture capital, where institutional funds have limited lives. Because VCTs have been around so long, their portfolios are full of companies of different ‘maturities’: in other words, investments are not all made (or exited) at the same time. This helps to flatten out the J-curve and enables smoother returns.

VCT portfolios are also full of companies with high levels of idiosyncratic risk. This doesn’t mean that they can’t be dragged down by a general malaise, as they were in 2008, but it does mean that it’s quite likely that the fortunes of different companies in a portfolio will diverge.

Could anything break this impressive run of performance? At our VCT seminars in Leeds, Birmingham and London, managers considered a number of headwinds.

Weighted average total return of all VCTs, share price and NAV, discrete calendar years, excluding 30% tax relief. Source: AIC/Morningstar.

The B-word

The subject of Brexit was never far away. No surprise there, given that our Leeds and Birmingham seminars were held in the week of Theresa May’s 230-vote defeat in the Commons, while our London event occurred the morning after MPs had to vote on no less than seven competing amendments aiming to influence the direction of Brexit.

Having listened to eight different VCT managers talk about the impact of Brexit on their portfolios, and read the views of two others, a couple of things struck me. Please note that both are generalisations.

Firstly, it’s not loss of access to EU markets that is the most important worry for VCT managers or their investee companies. This is partly because not all sell into Europe, and even for those that do, it might not be their most important market. (As I’ve said, there are exceptions.)

What has come up again and again, though, is the question of access to the talent of EU nationals. The UK in general, and London in particular, have benefitted from ready access to the talents of an entire continent (and beyond). If the attractiveness of the UK as a place to live and work were diminished, that would be a worry for VCT managers.

New rules bedding in

The other interesting theme to emerge from our seminars is the absorption of the ‘new rules’ into VCTs’ investment strategies. I’m talking about the 2015 age limit and ban on management buy-outs (MBOs), as well as the 2018 ‘risk to capital’ condition. While it’s true to say that these rules have pushed VCTs up the risk scale in general, many managers – especially those doing large fundraisings – believe that the effects on them will be minimal. That’s because they’ve always invested in a way that would be compliant with the new rules.

For those that haven’t, perhaps because they did more MBOs or followed strategies more focused on capital preservation, the new rules have had a number of effects. Fundraisings have generally been smaller. New hires have been made to refocus teams on earlier-stage opportunities. And naturally, investment strategies, including the sourcing of deals, have been reassessed.

Triple Point is an interesting case. The company’s new ‘challenge-led’ strategy aims to mitigate risk by investing in companies that solve the pre-existing problems of corporates (rather than companies with cool products or services in search of a market). But the investee companies themselves are early-stage, making the strategy entirely compliant with the new rules.

Not all of the rule changes are restrictive. For so-called ‘knowledge-intensive’ companies, the new rules are more liberal, with a looser age limit and the ability to raise more money from VCT and EIS.

Mixing it up

In addition to the VCT rule changes and Brexit, our seminars touched on a wide range of other issues affecting portfolio companies – both opportunities and threats. They are too numerous to go through here, and because VCTs’ portfolios are so diverse, perhaps they don’t matter as much to an investor as a VCT manager’s skill in being able to locate, develop and profitably exit their investments.

For example, in Leeds we heard about an eco-friendly weedkiller company, a cremation business, a maker of children’s TV programmes, and a company that helps John Lewis reduce queue times in its children’s shoe department. Clearly, the determinants of success or failure in each of these companies will be very different.

This kind of diversification, together with generous tax reliefs and the ability to access an asset class that’s unlikely to be represented otherwise in clients’ portfolios, are among the key attractions of VCTs. These attractions remain, despite Brexit worries and the challenges of the new rules.

Of course, nothing is guaranteed, and VCTs will always be high-risk. But their 23-year record has demonstrated that the evergreen closed-ended structure is absolutely the right one for this kind of investing, giving managers the maximum amount of control and long-term investors the best shot at a positive outcome.