So long MATE

As we covered on our Wednesday news post, this week saw JPMorgan Multi Asset Growth & Income (MATE) announce its merger with JPMorgan Global Growth & Income (JGGI). For fans of investment companies, this story may seem familiar as JGGI has already swallowed up the Scottish Investment Trust and JPMorgan Elect.

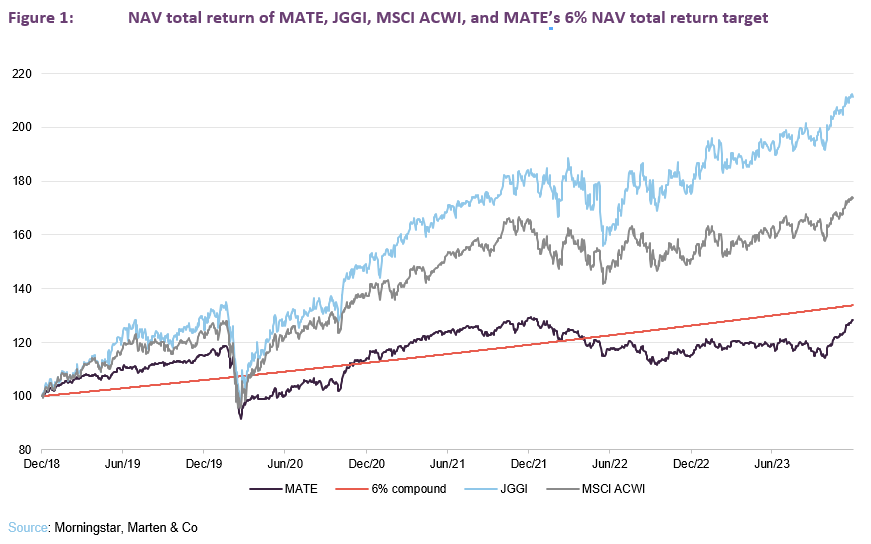

MATE’s board outlined several sensible reasons which, on the face of it, seem valid: greater scale and liquidity, cheaper fees, and a management fee waiver by JPMorgan to sweeten the deal. JGGI has also been a solid global equity strategy, with its NAV returns beating the MSCI All Countries World Index (ACWI) for the past five calendar years. As can be seen in Figure 1, MATE shareholders would have been better off historically holding JGGI, purely in terms of its capital growth. However, there is more to investing than chasing the tail of historic returns, and we can use the merger of MATE as a chance to examine why an apparently advantageous merger may still not be the best option for everyone.

One problem with the proposed merger from the perspective of MATE shareholders, and something that is arguably shared with some of the other recent mergers the trust universe has seen, is that there is quite a difference between the risk-return profiles of the two strategies or, put another way, they’re trying to achieve quite different things.

MATE is managed with more of a low volatility absolute return mindset – it aims to achieve total returns of 6% per annum (averaged over five years) with a target volatility two-thirds that of a global equity index (the MSCI ACWI). To achieve this, it invests in a broader range of asset types (think global government bonds, high yield bonds, global credit, infrastructure) than JGGI, which is focused on large and mega cap equities. MATE has sometimes struggled to achieve this, as can be seen in Figure 1, having been blindsided by both COVID-19 and the surge in inflation. However, the pandemic was an extreme market event, and inflation was at least in part a consequence of it (think of all the monetary and fiscal stimulus pumped in to prop up the global economy), so you would be hard pushed to find a strategy that wasn’t affected in some way.

JGGI is managed with more of a relative return mindset – it aims to outperform the MSCI ACWI over the longer-term on a total return basis.

One particular problem that MATE’s board identified was the pressure of having to generate a high dividend yield from revenue income. MATE underwent an adjustment to its investment approach in March 2021, that aimed to ease that requirement, allowing it to pay some of its dividend from capital. Similarly, JGGI’s managers do not have an income-generation requirement per se. It aims to achieve the best returns and then provide a dividend equal to 4% of NAV and can dip into capital when it needs to, to pay this.

In reality, the situation has been quite different to what was expected when the policy was set. The sudden return of inflation and central banks response to this has given rise to a period of higher volatility in asset prices across the board. This has meant that MATE’s NAV volatility was only 4% less than that of the MSCI ACWI, although 18% less than JGGI’s all-equity strategy. Given the gap between the performance of MATE, JGGI and the MSCI ACWI, MATE has generated the lowest risk-adjusted returns of the three (for those that like Sharpe ratios, MATE’s is 16 times lower than JGGI’s). This may explain MATE’s board’s decision to throw in the towel. It maybe that the board felt that MATE had not been delivering sufficient value to shareholders, and JGGI, which also benefits from the same house views of JPMorgan that drive MATE’s allocation, would likely represent a more attractive long-term investment opportunity. Also given MATE’s staunch defence of its discount, the trust was slowly cannibalising itself and shrinking an already small trust in the process, which could not be sustained indefinitely.

That said, MATE’s problems are not new, and its shareholders would have known about these when they approved its continuation in July last year. We were therefore surprised to see these proposals at this point, which seem to fly in the face of shareholders wishes, particularly at a time when the economic clouds darkening, which could finally see MATE come into its own. There must be a risk that investors could be switching into a more volatile equity strategy at a time when the outlook for equities is unpredictable.

MATE’s blend of bonds and equities will have also been key for some, as more cautious investors seldom place all their capital in pure equity strategies. For those with explicit allocation targets or risk budgets, JGGI may simply be unsuitable for them, even if its risk-adjusted returns are magnitudes higher.

In merging MATE with JGGI it seems MATE’s board have followed the path of least resistance, given the possible synergies and the waver JPMorgan has thrown in. However, one does wonder how much past performance played a role in board’s decision, as simply chasing historic returns is a well-trodden path to disaster. MATE had begun to show promising performance over the last 12 months and MATE shareholders may decide to take the opportunity to cash out and find another target return trust.

On a more fundamental level, MATE’s blend of bonds and equities will have also been key for some, as more cautious investors seldom place all their capital in pure equity strategies. For those with explicit allocation targets or risk budgets, JGGI may simply be un-investable for them, even if its risk-adjusted returns are magnitudes higher.